On Donald Trump and "Liberation Day"

How his second inaugural address was even darker than his first

Once, in a better, more graceful time, inaugural addresses had higher aims. In his second inaugural given during the waning days of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln called for national healing and metaphorically extended his large hands southward “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” Sixty-seven years later, Franklin Roosevelt rallied the country against fear wrought by the Great Depression. In 1961, John F. Kennedy outlined his vision for a New Frontier and set a seemingly impossible standard for future addresses. And after a bitter campaign and contested election that was only resolved by a still-controversial Supreme Court decision, the first act of George W. Bush’s presidency was to acknowledge outgoing president Bill Clinton’s service to the nation and recognize Bush’s opponent Al Gore “for a contest conducted with spirit and ended with grace.” Speeches like these had a three-fold mission: to show dignity, generosity and humility during the peaceful transfer of power; to set an agenda for the incoming president’s administration; and in the process, to strive for soaring rhetoric capable of raising the hair on listeners’ arms.

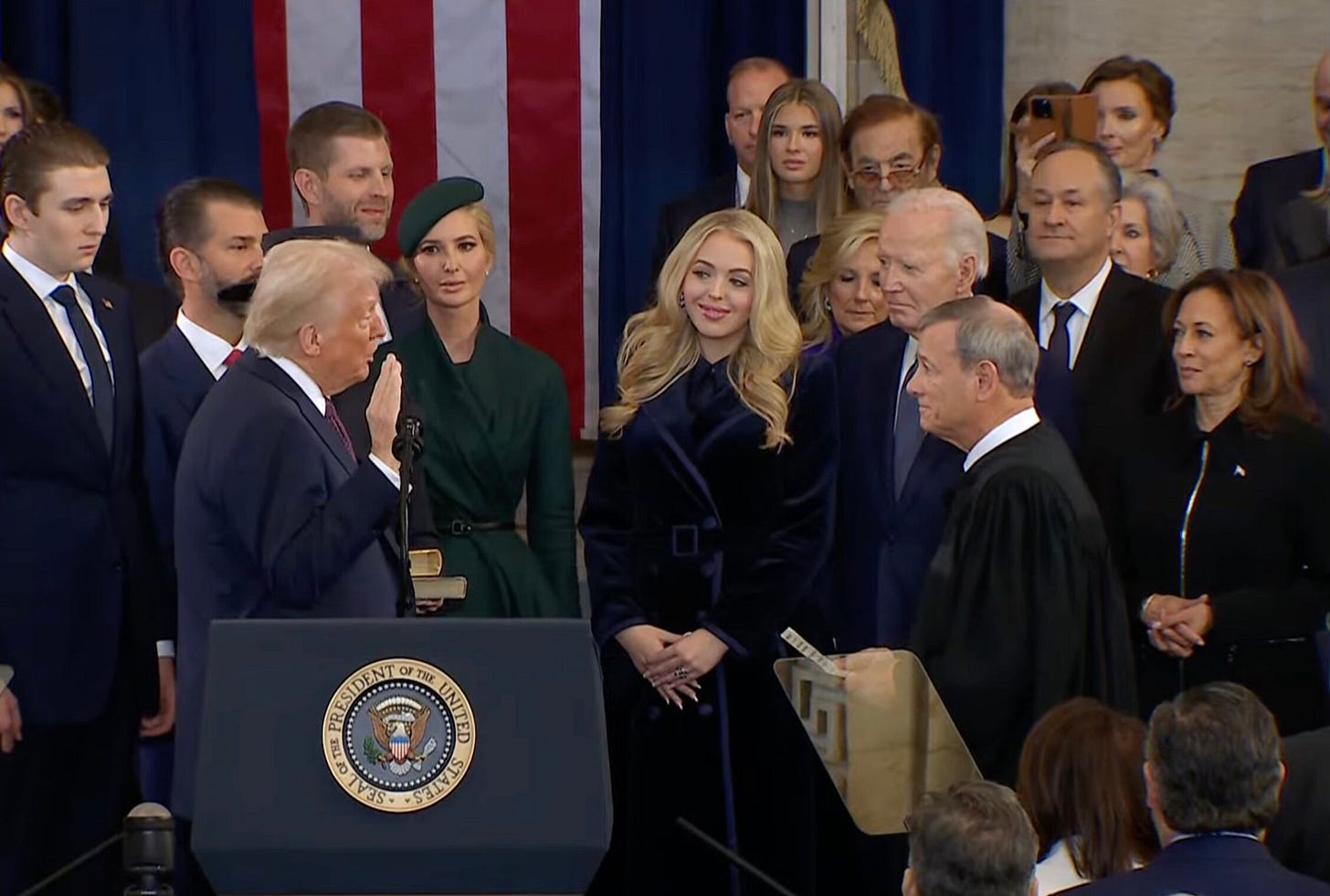

Like his first inaugural, Trump’s second address, given Monday inside a packed Capitol Rotunda due to frigid temperatures that had fallen on Washington, refused to pay much mind to niceties and tradition. After a bungled swearing-in that must surely have enraged the show business-minded Trump—the First Lady appeared to miss her cue to move forward to occupy the traditional place between her husband and Chief Justice Roberts, the Chief Justice began the oath early and Trump didn’t take the opportunity to place his left hand on the two Bibles, all of which created an awkward television tableau—launched into an address spiked with grievance and vengeance, and devoid of any attempt at poetry.

President Donald Trump takes the oath of office from Chief Justice John Roberts (Photo: PBS NewsHour broadcast)

This is to say the speech was quintessential Trump. Self-centered in focus, dark in tone, he refused to speak in the mode of Lincoln, Roosevelt, Kennedy or Bush. There was no mention of gratitude for the lengthy service of his predecessor. Nor was there an acknowledgment of his opponent Vice President Kamala Harris’s service or history-making campaign. (Clad in a somber, black pantsuit with a series of gleaming zippers, her face set and determined, she appeared as if she were going into battle.) Such bipartisan grace notes were replaced with barbs and attacks lobbed at Democrats and the Washington establishment that sounded more like red meat from the campaign trail.

His defeat of Harris in November, Trump said, “totally reverse[d] a horrible betrayal” that had taken place, seemingly by the Biden-Harris administration and its supporters: “For many years, a radical and corrupt establishment has extracted power and wealth from our citizens, while the pillars of our society lay broken and seemingly in complete disrepair.” When speaking of the Israel-Gaza ceasefire and the release of Israeli hostages held by Hamas for fifteen months, he refused to acknowledge his predecessor’s role in the deal. He assailed Biden, implying his administration had refused to provide “basic services” to “the wonderful people of North Carolina” in the wake of Hurricane Helene. Education under the outgoing administration had taught “children to be ashamed of themselves in many cases, to hate our country.” Monday was “Liberation Day” and, always the star in his own Marvel universe, Trump was the avenging hero who had endured and triumphed. Referencing the July assassination attempt in Butler, Pa., he declared, “I was saved by God to make America great again.”

To his supporters, the speech has been declared a success. On CNN just moments after the ceremony ended, Scott Jennings declared it “incredible,” crowing, “Watching Donald Trump indict these gangsters to their faces…was remarkable. They had to sit there and take it.”

One measure of a speech’s success is whether the speechwriter captured their employer’s voice. In this arena, at least, Trump’s address must be considered a resounding triumph. But in a good working relationship, the aide can also push the speaker to expand themselves—to rise to the occasion with ideas and phrases outside of their comfort zones. As a speechwriter to Ronald Reagan and, subsequently, George H.W. Bush, Peggy Noonan embroidered elegance into Bush’s speeches. Never a memorable public speaker, he nonetheless injected some poetry at the behest of Noonan into his 1988 Republican National Convention speech and, a few months later, his inaugural address, when he described America as “an endless, enduring dream and a thousand points of light.” His son George W. Bush, in partnership with David Frum and the late Michael Gerson, was at times able to transcend his jocular, plainspoken Texas style, such as when he used his first inaugural address to call for a better politics. “Civility is not a tactic or a sentiment,” he said. “It is the determined choice of trust over cynicism, of community over chaos. And this commitment, if we keep it, is a way to shared accomplishment.”

As he did eight years, Trump demonstrated he was not capable of such a partnership or exhibiting such grace. What he did do was set an agenda, built once again on a deep foundation of grievance and retribution. But even here he broke with precedent. In place of the broad, sweeping rhetoric that usually characterizes inaugurals and seeks to bring Republicans and Democrats together around a set of common goals—at least for the duration of the speech—Trump was granular, specific, outlining a list of divisive executive orders he pledged to sign along with other actions that would presumably right the ship of state: declaring a national emergency at the southern border, invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to designate “the cartels as foreign terrorist organizations,” declaring a national energy emergency to tap “that liquid gold under our feet,” revoking Biden’s 50% electric vehicle target, imposing tariffs and reclaiming ownership of the Panama Canal. In a comment that generated applause in the Rotunda—and prompted Trump’s 2016 opponent and former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton to burst out laughing—he pledged to rename the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America.

Perhaps even more alarming is what he apparently chose not to include. Speaking afterward to overflow attendees gathered in Emancipation Hall, Trump said he had also considered mentioning the “January 6 hostages” (to whom he granted sweeping clemency last night) and attacking Biden’s preemptive pardons of the House Select Committee—including former Republican Reps. Liz Cheney, whom he dubbed “a crying lunatic,” and “Crying Adam Kinzinger”—and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark A. Milley.

When measured against his first inaugural address in 2017, Trump seemed more subdued in delivery, perhaps a result of the move indoors to the cramped Rotunda. But he appeared less inhibited rhetorically. While there was no phrase to match “American carnage,” his vision of America remains as dark as ever and, as he has been signaling, is at once more expansive. “We will pursue our manifest destiny,” he proclaimed, declaring that America “will once again consider itself a growing nation.”

To call it “some weird shit,” as George W. Bush apparently deemed Trump’s 2017 address, is to rob the speech of how disturbing and unorthodox it was in both policy and style.

Of Kennedy’s inaugural, his speechwriter Ted Sorensen wrote, “The right speech, delivered at the right time by the right speaker, can ignite a fire, change men’s minds, open their eyes, alter their views, bring hope to their lives and, in all these ways, change the world. I know. I saw it happen.”

While few minds were likely changed, few eyes opened and few views altered, there is no denying that Trump brings hope to some people’s lives. In the first official act of his nonconsecutive second term, he was unconstrained, at once restored to the presidency and seemingly liberated from it by the virtue of being term-limited. No longer is he accountable to voters. Absent moments of bipartisan decency, high-minded talk of unity and democracy, and poetic flourishes, he was straightforward about what he intends to do: change the world in his own image.